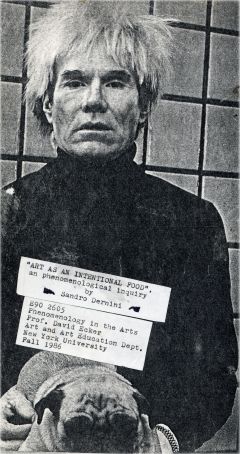

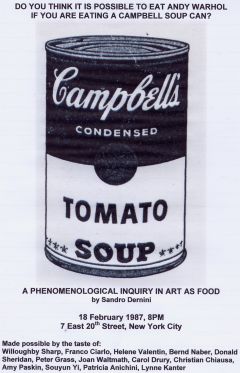

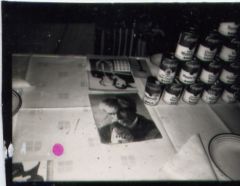

On 18 February 1987, in New York, at the Patrizia Anichini Gallery, I RITUALLY performed

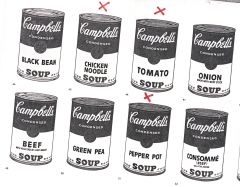

DO YOU THINK THAT IT IS POSSIBLE TO EAT ANDY WARHOL BY EATING A PLEXUS CAMPBOLL'S SOUP CAN?

as an aesthetic inquiry for my PhD course E90.2605 on Phenomenology and the Arts at New York University, directed by prof. David W. Ecker, to achieve a basic knowledge of the literature of phenomenological aesthetics and skills in phenomenological inquiry in the arts.

I prepared my phenomenological performance, by being inspired for moving forward my NYU Ph.D inquiry on "ART AS FOOD", by the symposium The Dematerialization of Art, organized the day after at New York University by Angiola Churchill and Jorge Glusberg, co-directors of ICASA (International Center for Advanced Studies in Art), where I was working as a graduate assistant of prof. Churchill, chair of the NYU Art and Art Education Dept.

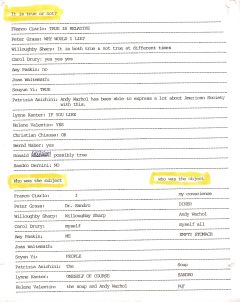

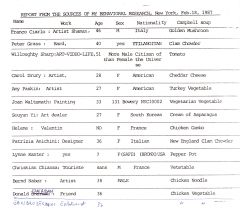

Invited artists were Willoughby Sharp, Helen Valentin, Bernd Naber, Franco Ciarlo, Donald Sheridan, Peter Grass, Lynne Kanter, Souyun Yi, Carol Drury, Amy Paskin, Christian Chiansa, and the host Patrizia Anichini.

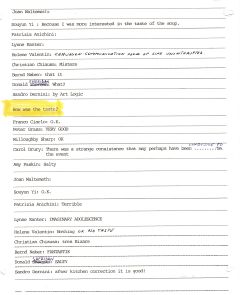

I prepared a questionnaire to be filled by participant artists after having cooked and eaten a Campbell's soup can. Seven questions I posed in the questionnaire, conceived for my phenomenological performance upon my NYU PhD course on Phenomenology and the Arts and my PhD reaserch study on "ART AS FOOD".

QUESTIONNAIRE

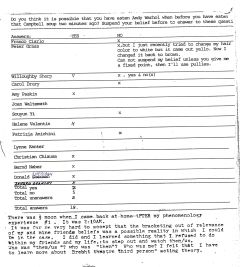

Do you think it is possible that you have eaten Andy Warhol when before you ate that Campbell soup two minutes ago?

- Suspend your belief before to answer to these questions. Answer: yes or no?

- What you mean?

- How do you know?

- How was the taste?

- Is it true or not?

-

Who was the subject? Who was the object?

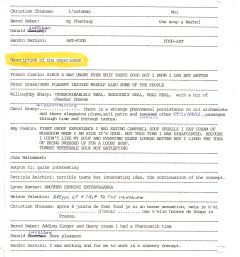

- Description of the experience

From questionnaires, came out that the majority of the participants believed that they "ate" Andy Warhol.

Few nights after, on 22 February 1987, Andy Warhol died!

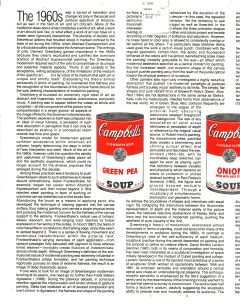

On 24 February, at the opening of the Dematerialization of Art Symposium, Lenny Horowitz and Stephen Di Lauro, two Plexus historical players, by reporting from the floor the Sandro's performance, questioned the panelists about this potential dematerialization of Andy Warhol into a Campbell's soup can.

The panelists were Jean Baudrillard, Donald Kuspit, Vito Acconci, Nam June Paik, Judy Barry, Dennis Oppenheim, Billy Kluver, Nancy Holt, Paul Taylor, Bruce Breland, Flor Bex, Rene Berger, Eika Billeter, Alan Bowness, Julie Lawson, Hervè Fischer and George Chaikin.

Nam June Paik, one of the speakers, answered believed possible that Andy Warhol had been dematerialized through the artist intentional act of eating his commodity art symbol.

“A Question to the Symposium on the Dematerialization of Art”

Art has its roots in ritual. We have only to look at the works of early shamans drawn on the walls of caves at Altamira and Lascaux. In addressing the idea of the dematerialization of art, aren’t we really taking about ritualistic art which cannot be repeated or preserved, setting aside for a moment the question of documentation, which is really a tool for raising capital. Take it a step further: the dematerialization of art is really ritual for the sake of ritual. Last night Sandro Dernini asked if when eating Campbell’s Soup, we are eating Andy Warhol—spoofing, if you will, the Christian communion ritual. This idea of concept of dematerialization as ritual is even further underscored in a performance, say, where 13 people gather to eat Campbell’s Soup. The soup has dematerialized into the stomachs of the participants and the gestures and words of those gathered have dematerialized into the air, not to be repeated again word for word, slurp for slurp. So the ritual dematerializes as it takes place. Dance, theatre—these stem from a need to ritualize, or make repeatable, certain words, movements, gestures. Another example, even more appropriate to the point I’m making raising this question with the panel, is the Plexus Art Operas, where hundreds of artists gather together to perform a theme. Dance, theatre, musical performance and visual arts are all combined here with the central idea of a modern sacrifice – sacrifice being an art ritual, of course. Bur the modern sacrifice of sacrifice, the end of ritual, really. So in talking about the dematerialization of art, aren’t we really talking about the demystification of ritual, the end of ritual. The impulse to include the audience, as in the happenings and the Living Theatre, is really the impulse of make shamans of us all, audience and artists alike. So, do you or do you not agree that the dematerialization of art is really art for the sake of demystifying, or even doing away with ritual, by making art? Whose Serpent? Who is the Serpent? Stephen DiLauro